Tracing the route of a 19th century in Central Java

Originally published in the Jakarta Globe, 26/05/12

Dark clouds are rolling

in across Central Java, and away to the north the smooth cone of Gunung Merapi

rises into a grey sky. I turn out of the

roaring flow of traffic on the main Yogyakarta-Solo highway, park my motorbike,

and make my way into the neatly tended gardens beyond. Ahead, the great black peaks of the Prambanan

temples tower above the treetops.

This vast 9th century Hindu temple complex is one

of Indonesia’s best known tourist attractions.

But it is a gloomy midweek afternoon; the tour buses have departed; the souvenir

hawkers have already gone home, and the place is almost deserted. It is a perfect moment to make the

connection, for I have come to Prambanan to trace the footsteps of another

foreign visitor, a British surveyor who trod these pathways exactly 200 years

ago.

***

At 9am on 19 January 1812, a similarly gloomy day,

Colonel Colin Mackenzie, a 57-year-old Scotsman serving as a military engineer

in the temporary British administration of Java, arrived at the little roadside

village of Prambanan. Mackenzie was a professional

soldier, but his real passion was archaeology.

He had come to Java tantalized by tales of relics out amongst the rice

fields.Prambanan was no lost city – princes from the Javanese courts often rode out for picnics amongst the ruins; a Dutchman named Hermanus Cornelius had made a preliminary survey in 1807, and just a few months before Mackenzie’s visit the first British emissary to Yogyakarta had noted the “ruins of several Hindoo Monuments and temples falling to pieces” beside the road. But now Mackenzie was about to embark on the exploration that would produce the first extensive account of Prambanan in English.

He and his companions, a Dutchman called Johan Knops, and an Anglo-Indian draughtsman called John Newman had arranged to stay with the Chinaman who ran the tollgate on the road nearby. Mackenzie – always an enthusiast – was so excited by the chance for a little practical archaeology that as soon as he arrived he dashed out alone across the road “to explore the field of Antique Research that lay displayed before me...”

***

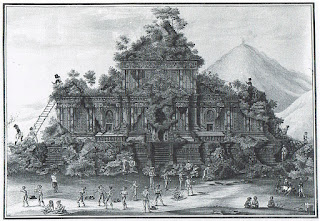

Thanks

to the extensive reconstructions of the 20th century the main

Prambanan complex, a trio of temples dedicated to the Hindu trinity of Brahma,

Vishnu and Siva, today looks much as it did when it was first built by the

artisans of the Sanjaya dynasty. But

Mackenzie described the structures as “vast mounds covered with Trees and

Bushes”, which only revealed themselves as “the vestiges and Debris of so many

once beautiful Temples” as the explorer drew close.As he traversed the terraces a group of local farmers began to follow Mackenzie. He spoke only a little pidgin Malay, while the locals spoke only Javanese. But they “seemed desirous of cultivating an amicable understanding”, and they led him to the largest of the temples and told him its popular name – Candi Loro Jonggrang, the Temple of the Slender Maiden.

Today this huge 47-metre hulk of masonry is fenced off after the damage caused by a 2006 earthquake. But there were no barriers in Mackenzie’s way: “I clambered higher, over vast heaps of the stones”, he wrote. He explored the inner chambers before heading back to the village, rounding up his companions, and setting out northwards once more, carried by the Chinese toll-keeper’s servants “in chairs provided with canopies of leaves”.

***

I make my own way northwards from the Loro Jonggrang temple on foot. The air is damp, and the clouds seem to be growing darker by the minute. A few gardeners are cutting the grass between the trees.

I am carrying a photocopy of Mackenzie’s notes, and as I reach the threshold of the Candi Sewu complex I catch my breath, for I recognize his description instantly. The gateway was flanked, Mackenzie wrote, by “two gigantic figures of porters, apparently resting on the knee on pedestals facing each other resting on clubs held in each hand”. It still is, and I pass between this pair of monstrous dwarapala guardians and into the avenues of miniature temples beyond.

By the time Mackenzie and his friends had finished sketching and measuring it was almost dark. They returned to the village “much fatigued tho’ highly gratified”, and that night they “enjoyed a profound repose undisturbed by any fears or want of security or any noise”.

I return in the same direction, collect my bike and head across the highway. This road was already the main link between Yogyakarta and Solo in 1812. Mackenzie noted that it was busy with horse carts and pedestrians, and lined with little booths “where Tea and Coffee, Rice boiled in heaps, Soups, Vegetables, Fruits, Nuts, Betel, the eternal Tobacco and the never failing Opium are prepared ready for the nourishment, comfort or intoxication of the weary traveller”. Today the road is flanked by cheap warungs and a huge, cream-colored mosque.

Just a kilometer to the south, however, the rice fields that Mackenzie traversed are still there. Mackenzie came here the morning after his exploration of Prambanan, with a “venerable Javanese” leading the way. I wonder, fancifully, if the gaggle of cheerful schoolchildren who point me in the right direction might be the descendants of my predecessor’s guide.

It was pouring with rain when Mackenzie visited this temple, and he “waded through the mire” to get there. Clambering out of the mud he spotted another monstrous dwarapala, and then stepped nervously into the inner chamber of the crumbling building: “it is not without awe,” he wrote, “that on looking up one perceives a thousand heavy blocks retained by little visible force just ready to tumble in and crush and overwhelm the curious Beholder.”

Today the place is a little more secure, after extensive restoration in the last decade. But I find Mackenzie’s dwarapala kneeling at the side of a well-kept garden.

***

From Candi Sojiwan Mackenzie and his companions headed south towards a great green rampart of hills, rising sharply from the rice fields. I follow suit, and I’m soon wending my way along a bumpy track through the forest. Eventually I reach a hidden back entrance to the vast Ratu Boko kraton complex, a mass of walls and foundations cut into the living rock on the westernmost promontory of the hills.

Mackenzie must have followed the same path, for he wrote of how he first stumbled upon a cave, carved in a cliff face, which his guide told him was used as a meditation chamber by the Sultan of Yogyakarta. The cave – Goa Lanang – is right next to the spot where I park my bike. I can hear the distant roar of the road, and see rooftops and minarets rising into a fine lavender haze from the great sweep of green country below.

From here Mackenzie returned to Prambanan village. He spent the following morning making a last series of sketches, before heading back to the east. He was a busy man, and he had an appointment at the Solo Kraton. Within a few months he would be called upon to plan the British attack on Yogyakarta of June 1812, and he would then be ordered to make a full survey of Java’s agricultural lands, before sailing back to India in 1813 to become Surveyor-General.

Before he left Java, Mackenzie, who had been a bachelor his entire life, married a locally born Indo-Dutch girl named Petronella Jacomina Bartels. She was 43 years his junior, and when he died of fever in Calcutta in 1821 she inherited his minor fortune.

Today Mackenzie is remembered for his extensive surveying work in in India, where he helped to lay the foundations of academic study of Hindu architecture. But for me, on this damp and sticky afternoon, it is his role as the first English-speaking foreigner to describe the temples of Central Java – and his palpable, boyish enthusiasm for the task – that makes him such an intriguing character.

As Mackenzie left Prambanan on 21 January 1812 he did so with “with mixed emotions of regret and pleasure”.

“It was not without reluctance I left these interesting ruins,” he wrote. Two hundred years later, I make my way slowly back down the green hillside towards the roaring traffic of the 21st century in similar frame of mind.

No comments:

Post a Comment